I’ve never enjoyed fasting on Yom Kippur. For several years I fasted because my parents did. My mum and dad always referred to it as a welcomed yearly cleanse and enjoyed their rituals that they’d created around the holiday over the years. For some years when I lived at home with them post university, I’d participate in their tradition. We didn’t go to synagogue, and we generally broke the fast early, around 4p. But every year I couldn’t ignore the fact that it felt as though it wasn’t fully serving me.

If you can’t already tell, I wasn’t raised religious—in fact, when my mother converted shortly before I was born, my grandmother begged her one thing. “Just promise me that you will not turn my son into a religious Jew”. So my mum converted with a reform synagogue that in the end rendered my sister and I “technically not Jewish by law”. After many years of wondering where I fit in, I realized that the thing I love most about Judaism is that for many of us it’s never really been about religion at all—it’s about the cultural connection, the diasporic community around us—the weaving of an intricate, adaptive tapestry that has been delicately pieced together across time and space in all of the places our families have (sometimes been forced to call)ed home.

And so, one Yom Kippur, I decided to drop the ritual of fasting. I decided instead to mark the day in my own way, creating a new tradition that perhaps I might pass down to my own kids. I wove yoga and meditation and breath work into this new part of the tapestry, and wrote in my journal reflecting on the year past. I wrote about what I planned to leave behind and what I hoped to carry with me into the new year, and, arguably most importantly, I always found a way to be in nature. And over the past nine years, this became my little tradition.

This year I was grappling with a continued feeling of loneliness that I have come to feel deep in my bones since last October. I spent every Jewish holiday in 5784 introducing my traditions to many people who were unfamiliar with our ways, and it was beautiful, but what I really yearned for—what I needed in this delicate time, was to be held in a more nutritive way, cradled by a community who had a baseline understanding of what it means to be “me”—a cultural Jew who feels nomadic in her heart continuously searching for home. To be surrounded by people who wouldn’t question my grief, and I didn’t have to teach. I ached for long tables filled with friends and family, and to feel some form of joy in a year that has felt incredibly dark and isolating. So I wrote about this in my journal after a quick meditation session. I recalled the sweet luck of discovering Shtick was hosting a new year dinner the week prior and my privilege to snag the last spot at their lush and diverse Rosh Hashanah table. I reminisced on my bite into a slice of juicy dragon fruit and the wonderful and robust blessing we received by way of the sound of the shofar. I felt my heart burst remembering our dance party after filling our bellies with delicious foods of the diaspora and could have screamed in delight when a Mizrachi song filled the speakers. This night was and is how I intend for my new year to feel.

After my journaling felt complete, I took a walk in the woods. Somewhere in New York. It was very quiet, devoid of people. I zoned into the sound of crunching leaves underneath my Birkenstocks and felt the tinge of coolness in the air. I allowed myself to feel sad for a little about the fact that I wished that I could be breaking the fast with my family in Kfar Saba like I did two years ago. I remembered the way the delicious warm air enrobed my body as we all sat at the table to engage in my Israeli family’s tradition of eating a spoon of my safta’s homemade rose jam—the petals of which are collected by my aunt throughout the year from a bush that grows right on the patio we sat on.

“Aba!” I heard a girl yell out. I looked ahead, and underneath the golden trees stood a man running down the path like a child, arms outstretched to catch the air. He turned to his family, smiling wide. His daughter signaled for him to make a path for us to pass, and as I walked past the mother and her two daughters offering a greeting.

“Gmar Chatima Tova” I smiled and continued walking. Moments later, I felt a tap on my shoulder. “How do you know Hebrew?” The mother asked. I explained to her my background, and soon we learned that our names were quite similar. “I’m Maayan!” she excitedly shared. And they were visiting from Israel for a couple of weeks.

“I feel like I can finally breathe here” Maayan shared with me. “For once in a very long time I can take a walk and not worry about where to go if I need to find shelter.” She sighed deeply, and I could feel the grief she was carrying. For all of it. For every single life lost, no matter who they are, for the children, for the families left broken forever. Life is not the same.

And it was here, in the middle of the woods in upstate New York that I felt as though the universe had intentionally placed someone who was carrying the same grief I have been carrying into my path. I felt permission to fully feel the weight of this past year on Yom Kippur in community—even if it was a small one made up of just a handful of us. For a moment we could simply be humans, holding on to a common thread of our tapestry, observing the insurmountable pain and wishes for the future, together.

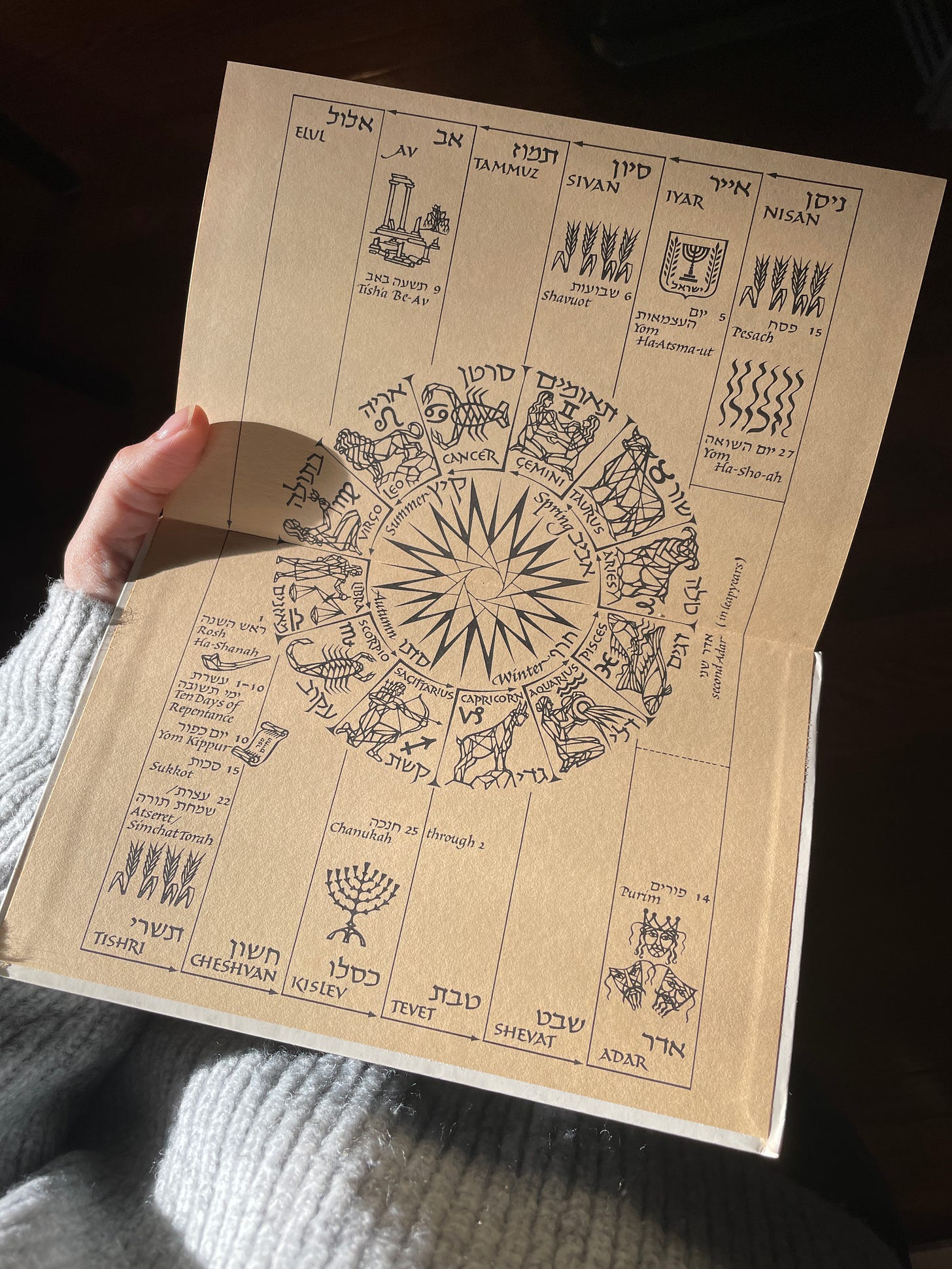

We parted ways, and I knew that I had been gifted this moment to remind me what being Jewish means to me. Celebrating Judaism is about honoring it’s diasporic nature. It’s about finding community wherever and whenever you can and gathering to celebrate often. It’s following the cycle of the moon and the seasons and honoring its indigenous nature. Judaism, by default, is community-centered. Meeting Maayan and her family in the forest reminded me that although I wasn’t able to be at the table with my own family, I had been granted the opportunity to weave another part of our tapestry in the woods with a part of my tribe across oceans and forests, creating another rich point of connection.

This year, in 5785, I promise to keep remembering my power to weave my story into the fabric of our collective identity. Because we are never truly alone.

Shabbat Shalom.